India has officially ascended to the world’s 4th largest economy, surpassing Japan with a nominal GDP of approximately $4.19 trillion in 2025.

The champagne corks are popping, the press releases are flowing, and the triumphalism is palpable.

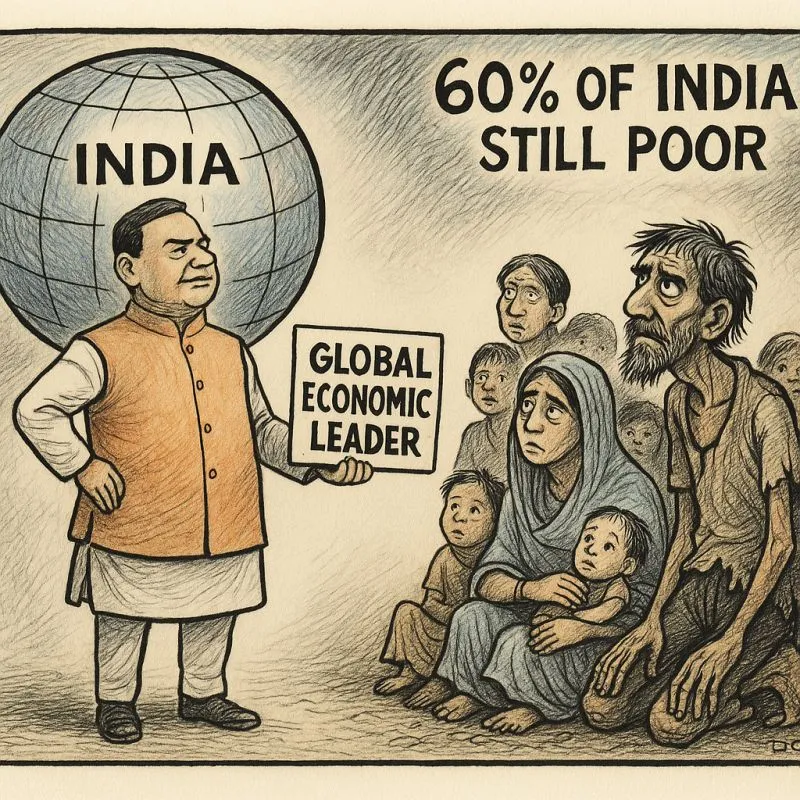

But here’s the uncomfortable question nobody seems eager to ask: What exactly are we celebrating?

Is it that the average Indian now earns around $2,880 per year while their Japanese counterpart takes home $34,000—a ratio of roughly 1:12? Or perhaps we’re toasting the fact that India ranks 130th out of 193 countries on the Human Development Index, nestled comfortably in the “medium human development” category? Maybe the festivities are for our 105th position in the Global Hunger Index, where 35.5% of our children under five are stunted, and we share the “serious hunger” category with Pakistan and Afghanistan?

The GDP metric, that darling of economists and policymakers, has performed a spectacular magic trick. It has convinced us that because our collective economic output has crossed an arbitrary threshold, we have somehow achieved something remarkable.

But GDP doesn’t ask: Who is this growth for? Where is it going? And crucially, is anyone actually eating better because of it?

Well,

India’s rise to 4th place is not primarily a story of prosperity; it’s a story of arithmetic.

With 1.43 billion people—the world’s largest population—even modest individual contributions create impressive collective totals.

Think of it this way: If every Indian contributed just $1,000 annually to GDP, we’d have a $1.4 trillion economy. At $2,000, we’re at $2.8 trillion. The math is remarkably simple. Japan, with just 123 million people, needs each citizen to be economically productive at levels nearly twelve times higher than India to maintain a comparable GDP.

This isn’t an achievement of economic sophistication—it’s demographic destiny.

When China reached the $4 trillion mark, its per capita income stood at approximately $3,500. Today, China’s per capita exceeds $13,000 while its economy has ballooned to over $19 trillion. India’s trajectory appears starkly different. We’ve achieved the size milestone without the corresponding individual prosperity gains.

Consider this thought experiment: If India’s population were the same as Japan’s (123 million), with our current per capita GDP of approximately $2,880, our total GDP would be merely $354 billion—roughly the size of Nigeria’s economy. Suddenly, the fourth-place trophy doesn’t shine quite so brightly.

The Per Capita Paradox!

India’s GDP per capita of $2,880 is a mean average—a number that can be wildly misleading in a country of extreme inequality. According to research from the World Inequality Lab, the top 1% of Indians control approximately 40% of the nation’s wealth, while the bottom 50% own just 3%.

If India’s GDP is $4.19 trillion and the top 1% controls 40% of national income (approximately $1.68 trillion), that leaves $2.51 trillion for the remaining 99%—nearly 1.42 billion people. This works out to a per capita GDP of roughly $1,768 for the vast majority. Remove the top 5%, who control about 62% of national wealth, and you’re looking at per capita figures closer to $1,100 annually—less than ₹1 lakh per year.

This is why the government provides free food grains to 80 crores (800 million) Indians. The celebrated 4th largest economy cannot feed its citizens without massive welfare interventions.

Whereas,

Germany’s per capita GDP exceeds $56,000. Japan’s is over $34,000. Even when we adjust for purchasing power parity (PPP)—a generous metric that accounts for lower living costs in India—we’re still at approximately $11,940 compared to Japan’s $53,060.

The question becomes unavoidable: In what meaningful sense are we a “large” economy when our citizens are, on average, twenty times poorer than those in truly developed economies? India’s GDP growth model has created a peculiar paradox—sectors that generate the highest GDP contribute the least to employment. Nearly 45% of India’s workforce toils in agriculture, which contributes merely 18% to GDP. Meanwhile, capital-intensive sectors like IT, finance, and real estate contribute over 50% to GDP while employing only 30% of the workforce, predominantly concentrated in urban centers.

This structural distortion means economic growth statistics become divorced from lived experience. The IT sector can boom, stock markets can soar, and GDP figures can climb—all while the vast majority of Indians see minimal improvement in their circumstances.

Youth unemployment tells an even grimmer story, hovering around 15-18% for graduates. Approximately 90% of India’s workforce remains in the informal sector, trapped in jobs with limited productivity, income security, or social protection. These aren’t statistics; they’re millions of educated young people with degrees and no prospects, their potential wasted in an economy that counts their existence but doesn’t create space for their ambition.

Female labour force participation at around 26% (recently updated to 41.7% but still significantly below global averages) means half the population is economically side-lined, dramatically constraining household incomes and overall growth potential.

If GDP were a meaningful measure of national success, India’s global rankings on human development indicators should roughly correlate. They don’t. Not even remotely.

Human Development Index: 130th out of 193 countries, firmly in the “medium human development” category with an HDI value of 0.685. Inequality reduces India’s HDI by 30.7%—one of the highest losses in the region. Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka—all with smaller economies—rank alongside or better than India in HDI.

Global Hunger Index: 105th out of 127 countries with a score of 27.3, categorized as “serious.” 13.7% of the population is undernourished, 35.5% of children under five are stunted, 18.7% are wasted, and 2.9% of children die before their fifth birthday. These aren’t abstract numbers—they represent millions of children whose physical and cognitive development has been permanently compromised by malnutrition.

Infrastructure and Services: Despite being the “fourth-largest economy,” India spends significantly less on health and education than recommended minimums. Healthcare expenditure hovers around 1.8% of GDP (WHO recommends 3%), while education spending is approximately 4.6% (against the National Education Policy target of 6%).

The cognitive dissonance is staggering. We’re simultaneously a trillion-dollar economy and a nation where one in three children is stunted from malnutrition. We’re an economic powerhouse where millions lack access to basic sanitation, clean water, and electricity.

When Growth Becomes Grotesque?

The top 1% of Indians hold over 40% of the country’s total wealth, while the bottom 50% hold just 3%. India now has 119 billionaires whose fortunes have increased almost tenfold over the past decade, even as real wages for the majority have stagnated or declined.

The World Inequality Report reveals that inequality in India has been accelerating since the early 2000s, with a particularly sharp concentration among the billionaire class—a phenomenon researchers term the “Billionaire Raj.” Female workers earn only 63 paise for every rupee earned by male workers, adding gender inequality to the economic equation.

This isn’t merely a moral failing; it’s an economic disaster. Extreme concentration of wealth means limited domestic consumption, as the rich save rather than spend proportionally, while the poor lack purchasing power. It creates markets too small to sustain domestic industry, forces over-reliance on exports, and generates social instability that ultimately threatens growth itself.

The United States offers a cautionary tale. Despite a GDP per capita exceeding $89,000, 38 million Americans live in poverty, medical bankruptcies remain common, and parts of the country struggle with crumbling infrastructure. India seems determined to replicate these mistakes at a far earlier stage of development.

The GDP Mythology: What This Number Actually Measures (and Doesn’t)

GDP measures economic activity—the total value of goods and services produced. But activity isn’t automatically beneficial. If pollution increases hospital admissions, GDP rises. If traffic congestion worsens, fuel consumption increases, and GDP rises. If inequality forces families to spend more on private security, education, and healthcare, GDP rises.

GDP doesn’t measure:

-

Distribution of wealth or income

-

Environmental sustainability or degradation

-

Quality of life, happiness, or well-being

-

Unpaid care work (predominantly performed by women)

-

Access to essential services like healthcare and education

-

Social cohesion, trust, or stability

Bhutan famously measures Gross National Happiness instead of GDP. While that might seem quaint, it acknowledges a fundamental truth: economic activity is a means to an end—human flourishing—not an end in itself.

India’s GDP milestone tells us our economy is active. It doesn’t tell us if that activity is making life better for most Indians. Based on every other development indicator, the answer appears to be: not really.

What Peer Countries Actually Look Like?

China (2nd largest): Per capita GDP of approximately $13,000; lifted 800 million people out of poverty in four decades; infrastructure that’s the envy of the developed world; manufacturing capabilities that make it the workshop of the world.

Japan (5th largest): Per capita GDP of $34,000; universal healthcare; life expectancy of 85 years; virtually zero poverty; infrastructure so advanced that trains apologize for being seconds late.

Germany (3rd largest): Per capita GDP of $56,000; world-class manufacturing; strong social safety nets; among the lowest inequality levels in the developed world.

India (4th largest): Per capita GDP of $2,880; 800 million people dependent on subsidized food grains; 105th in Global Hunger Index; 130th in HDI; infrastructure development decades behind peers.

The comparison isn’t flattering.

We’re in a category by virtue of size alone, not by any measure of economic sophistication, citizen welfare, or development outcomes. Perhaps the most devastating critique of India’s GDP story is this: we’re growing without creating adequate quality employment. The demographic dividend we constantly celebrate—India’s young population—is rapidly becoming a demographic disaster.

Educated youth graduating by the millions into an economy that cannot absorb them. Engineering graduates driving Uber. MBAs working in call centers. PhD holders competing for government clerk positions where tens of thousands apply for handfuls of jobs.

India’s unemployment rate remained @ 3.2% in 2023-24 according to official statistics, but these numbers are misleading. They count anyone who worked even one hour in the week preceding the survey as employed. They classify unpaid helpers in household enterprises as employed. They don’t capture underemployment or the quality of employment.

The real story is in disguised unemployment, where people are technically working but contributing minimal value and earning less than living wages. It’s in the 57.3% of workers who are self-employed—many not by choice but by necessity, eking out survival rather than building prosperity.

Leverage We Don’t Actually Have!

Optimists argue that becoming the fourth-largest economy enhances India’s global standing, strengthens our role in supply chains, and increases our influence in multilateral institutions. Does it?

Our economic size should theoretically give us negotiating power. But power requires more than aggregate numbers—it requires resilience, technological capability, manufacturing depth, and consumer market strength.

When global tech companies look for manufacturing bases, they increasingly choose Vietnam over India despite our larger market. When countries negotiate trade deals, they value quality of infrastructure, ease of doing business, and skilled workforce—all areas where India lags behind much smaller economies.

Our forex reserves and stock market valuations look impressive until you realize they’re disproportionately benefiting the top 10% of society. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) fell by over 96% in 2024-25, primarily due to policy uncertainties and global risk aversion.

The global stage doesn’t care about aggregate GDP. It cares about capabilities, reliability, and value addition—metrics on which India’s performance remains mediocre.

Admitting the Problem Before Solving It

The first step toward meaningful progress is honest diagnosis. India’s GDP ranking is not an achievement to celebrate; it’s a baseline to improve from. It reveals the potential of 1.4 billion people while simultaneously exposing how far we are from realizing that potential.

Real success would look like:

-

Reducing the HDI gap from 30.7% loss due to inequality

-

Moving from 105th to at least top 50 in Global Hunger Index

-

Increasing per capita GDP from $2,880 to at least $8,000-10,000 within a decade

-

Creating 10-15 million quality jobs annually to absorb new workforce entrants

-

Raising health spending to 3% of GDP and education to 6%

-

Achieving female labour force participation rates above 50%

-

Reducing the Gini coefficient from current levels (various estimates from 0.339 to 0.472) to below 0.30

Dr. Jaimine Vaishnav is a faculty of geopolitics and world economy and other liberal arts subjects, a researcher with publications in SCI and ABDC journals, and an author of 6 books specializing in informal economies, mass media, and street entrepreneurship. With over a decade of experience as an academic and options trader, he is keen on bridging the grassroots business practices with global economic thought. His work emphasizes resilience, innovation, and human action in everyday human life. He can be contacted on jaiminism@hotmail.co.in for further communication.

Dr. Jaimine Vaishnav is a faculty of geopolitics and world economy and other liberal arts subjects, a researcher with publications in SCI and ABDC journals, and an author of 6 books specializing in informal economies, mass media, and street entrepreneurship. With over a decade of experience as an academic and options trader, he is keen on bridging the grassroots business practices with global economic thought. His work emphasizes resilience, innovation, and human action in everyday human life. He can be contacted on jaiminism@hotmail.co.in for further communication.