Think about this for a second — do you still remember that one mean thing someone said to you years ago? Maybe it was a classmate calling you “lazy,” a boss saying you “weren’t ready,” or a friend who made a joke that didn’t feel like a joke. Now, try recalling the last five compliments you got. Harder, right?

That’s not just you being sensitive. It’s how your brain is wired.

Science says our minds are built to cling to insults and let go of praise. A rude comment can echo in your head for decades, while a kind word fades away in just weeks. It sounds unfair — but there’s a fascinating reason behind it.

1. Our brain has a “bad news” bias

Our brains are like Velcro for bad memories and Teflon for good ones.

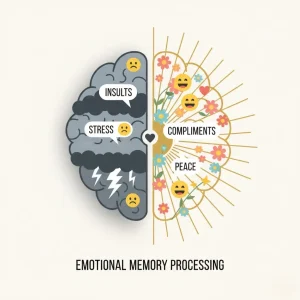

This phenomenon, called negativity bias, means we naturally give more weight to negative experiences. Even if nine people love your work and one person criticizes it, your mind zooms in on that single critic like a spotlight. It’s not a flaw; it’s a built-in survival trick from ancient times.

2. Why insults hit harder

When someone insults you, your amygdala — the brain’s fear center — immediately jumps into action. It treats the insult as a potential threat. The brain releases stress hormones like cortisol, your heartbeat quickens, and your mind stores the moment in extra detail. That’s why, even years later, recalling that insult can still make your chest tighten or your stomach drop.

Meanwhile, compliments don’t trigger any danger alarms. Your brain doesn’t feel the need to “remember” them for survival. So it logs them lightly, then quietly moves on.

3. Evolution made us this way

A long time ago, remembering bad stuff literally kept people alive.

If you remembered which berries made you sick or which animal chased you, you survived. Forgetting danger was deadly. So our ancestors’ brains evolved to spot threats faster and remember them longer.

Fast-forward a few thousand years — now the “threats” are no longer wild animals but awkward comments, failed interviews, or mean texts. Yet our brains still react like it’s a matter of life and death.