There’s a particular kind of nausea that comes from reading the Epstein files. Not just from the allegations themselves—though those are stomach-turning enough—but from the creeping recognition that we’ve seen this movie before. We know how it ends. There will be outrage, breathless cable news segments, Twitter storms, maybe a few sacrificial lambs. Then silence. Then business as usual. The same politicians will get elected. The same celebrities will sell out stadiums. The same titans of industry will give TED talks about innovation and progress.

We pretend to be shocked, but we’re not. Not really. What shocks us is being forced to look directly at something we’ve always known was there.

The sociologist Pierre Bourdieu had a term for this: “symbolic violence.” It’s the kind of harm that doesn’t announce itself with a raised fist. Instead, it’s woven into the fabric of how society operates, so thoroughly normalized that it becomes invisible. When we talk about “networking” or “connections” or “influence,” we’re often describing systems where access to power is traded like currency—and where some people, particularly young women with few resources, become the currency itself.

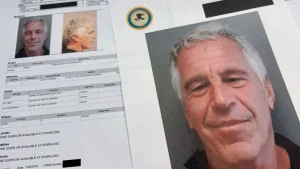

The Epstein files lay bare this exchange in such explicit terms that we can’t dress it up in euphemisms. Here was a man who allegedly created an entire infrastructure for exploitation, complete with private planes, private islands, and a contact list that read like a who’s who of global power. What the documents reveal isn’t an aberration. It’s a window into how power actually works when you strip away the PR departments and the carefully managed public images.

When sociologists talk about “elite deviance,” they’re describing misconduct by people at the top of social hierarchies. Here’s what makes elite deviance different from regular crime: the higher up you go, the less the rules seem to apply. This isn’t a bug in the system. It’s a feature.

Psychologists call this “moral disengagement”—a set of mental tricks we use to do harmful things without feeling bad about ourselves. There are several flavors: We convince ourselves that our actions don’t really count as wrong (“It’s not like anyone got seriously hurt”). We minimize the consequences (“She seemed fine with it”). We dehumanize the victims (“These girls knew what they were doing”). We diffuse responsibility (“Everyone else was doing it too”).

But here’s the truly sinister part: the higher your status, the easier these psychological gymnastics become. When you’re surrounded by people who benefit from the same system, you create what social psychologists call “pluralistic ignorance”—everyone privately suspects something’s wrong, but because no one speaks up, everyone assumes the behavior must be acceptable.

The Epstein network allegedly operated in precisely this environment. Wealth insulated. Celebrity provided cover. Political connections offered insurance. This isn’t conspiracy theory; it’s how elite networks function. The historian C. Wright Mills called it “the power elite”—overlapping circles of political, economic, and military leaders who move in the same spaces, attend the same parties, sit on each other’s boards, and protect mutual interests.

Why Governments Won’t Act (Not Really)!

We keep waiting for governments to deliver justice, to clean house, to restore order. We’ll be waiting a long time. Here’s why.

First, there’s “regulatory capture”—a situation where the agencies meant to oversee powerful institutions become dominated by the very interests they’re supposed to regulate. Swap “regulatory” for “political” and you get the same dynamic. The people making and enforcing laws are often embedded in the same social networks as the people who should be investigated.

Second, there’s what political scientists call “elite consensus”—the largely unspoken agreement among people in power about which issues matter and which boundaries cannot be crossed. You can have fierce partisan battles about tax rates or immigration policy, but fundamental threats to the power structure itself? Those get quietly shelved.

Third, and perhaps most cynically, there’s electoral calculation. Prosecuting beloved celebrities or politically connected figures is risky. It alienates donors. It creates enemies. It might even backfire if the public decides they’d rather not know. Politicians are exquisitely attuned to what voters actually want versus what they say they want. And the brutal truth is that most people would rather preserve their illusions than confront uncomfortable realities.

When documents do get released, when investigations do happen, they’re often carefully stage-managed. Release enough to satisfy public anger, but not so much that the whole edifice comes tumbling down. Sacrifice the already-dead or the already-discredited. Protect everyone else. It’s a pressure release valve, not a reckoning.

The Theology of Power!

Now for the uncomfortable bit: why would God enjoy this?

I don’t actually think God enjoys it—but I think the question reveals something crucial about how power operates. Throughout history, the powerful have claimed divine sanction for their actions. Kings ruled by divine right. Wealth was a sign of God’s favor. Suffering was part of God’s plan.

This is what sociologists call “theodicy”—a justification for why bad things happen. Every social order needs one. If you’re on top, theodicy explains why you deserve to be there (you’re smarter, you work harder, God chose you). If you’re on the bottom, it explains why you need to accept your position (it’s character-building, it’s karma, God works in mysterious ways).

The really perverse thing is how theodicy functions even in our supposedly secular age. We don’t invoke God directly anymore, but we invoke the Market, or Meritocracy, or Evolution. We tell ourselves that people who succeed must deserve it, and people who suffer must somehow be at fault. This is what psychologists call the “just-world hypothesis”—our deep need to believe the world is fair, even when evidence suggests otherwise.

When powerful men exploit vulnerable women and girls, our theodicy kicks in: Those girls must have wanted something. They were seeking attention. They should have known better. It’s a psychologically convenient narrative because it means the world still makes sense. The alternative—that predation is baked into power structures, that nice-seeming successful people can do monstrous things, that the institutions we trust are compromised—is too destabilizing to accept.

If God exists and enjoys any of this, it’s only the version of God we’ve created in our own image: A God who sanctifies power and blames victims.

The Spectacle of Debate

Here’s what will happen next, because it’s what always happens. There will be debate. Endless debate.

Op-eds will be written (like this one). Panels will be assembled. Everyone will have takes, hot and lukewarm. We’ll debate whether so-and-so definitely knew or probably didn’t know. We’ll debate what “association” really means. We’ll debate whether a single photo means anything. We’ll debate the credibility of accusers, the reliability of documents, the motivations of journalists.

The French theorist Guy Debord called this “the society of the spectacle”—a world where genuine experience gets replaced by representations, where everything becomes a show to be consumed. We’re not actually dealing with the problem; we’re watching ourselves deal with the problem. We’re performing outrage, performing concern, performing serious deliberation.

Debate serves a function: it creates the impression of engagement while preventing actual change. As long as we’re still debating whether something happened, we don’t have to address why it keeps happening. As long as we’re focused on individual bad actors, we don’t have to examine systemic rot.

This is “discursive closure”—the way certain conversations, no matter how much noise they generate, never actually threaten the status quo. We debate endlessly but within carefully policed boundaries. We can talk about individual predators but not patriarchy. We can talk about bad apples but not poisoned orchards.

Why We Move On?

And we will move on. We always do.

There’s a concept in psychology called “psychic numbing”—the more people who suffer, the less we care about any individual victim. One child’s story breaks our heart. Thousands become a statistic. It’s a protective mechanism; if we truly felt the weight of all the world’s suffering, we’d be paralyzed.

But there’s also something more insidious at work: “motivated forgetting.” We don’t just passively forget; we actively choose to forget things that threaten our comfort or our worldview. The Epstein story threatens a lot. It threatens our belief that success indicates virtue. It threatens our trust in institutions. It threatens our parasocial relationships with celebrities. It forces us to confront questions about complicity and silence.

Forgetting is easier. Especially when the culture provides convenient amnesia aids. New scandals will emerge. New crises will demand attention. Our feeds will refresh. Algorithms will serve up the next outrage, and the next, until this one becomes just another entry in an ever-growing catalogue of things we’re vaguely aware happened.

There’s also what sociologists call “legitimation crisis”—when institutions lose credibility, when the gap between stated values and actual practice becomes too obvious to ignore. This should be a moment of fundamental reckoning. But legitimation crises rarely lead to revolution. More often, they lead to exhaustion. People can only sustain outrage for so long before cynicism sets in.

Cynicism is comfortable. It asks nothing of us. It lets us feel superior (we weren’t fooled like those naive people) while absolving us of responsibility (the system’s too corrupt to fix anyway, so why bother?).

Dr. Jaimine Vaishnav is a faculty of geopolitics and world economy and other liberal arts subjects, a researcher with publications in SCI and ABDC journals, and an author of 6 books specializing in informal economies, mass media, and street entrepreneurship. With over a decade of experience as an academic and options trader, he is keen on bridging the grassroots business practices with global economic thought. His work emphasizes resilience, innovation, and human action in everyday human life. He can be contacted on jaiminism@hotmail.co.in for further communication.

Dr. Jaimine Vaishnav is a faculty of geopolitics and world economy and other liberal arts subjects, a researcher with publications in SCI and ABDC journals, and an author of 6 books specializing in informal economies, mass media, and street entrepreneurship. With over a decade of experience as an academic and options trader, he is keen on bridging the grassroots business practices with global economic thought. His work emphasizes resilience, innovation, and human action in everyday human life. He can be contacted on jaiminism@hotmail.co.in for further communication.