The political transition marked by Bangladesh’s general election of 12 February, 2026, represents not merely a change of government, but a broader moment of recalibration in South Asian geopolitics.

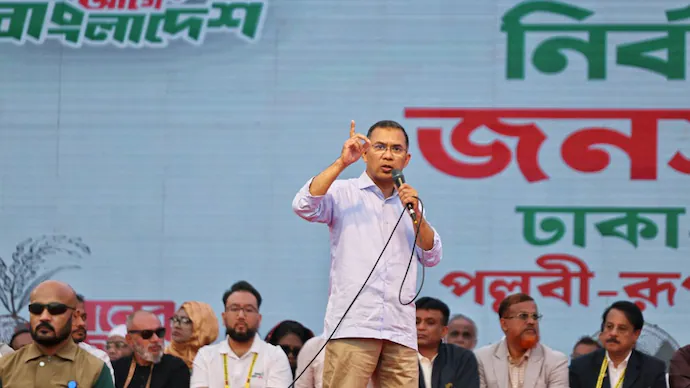

With the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) securing a decisive parliamentary majority—winning 212 of 299 seats in a landslide—and Tarique Rahman returning from 17 years of exile in London to assume leadership as prime minister-designate, the outcome invites reflection on how regional relationships evolve—and how they can be better managed.

Rather than attributing the election result solely to episodic unrest or personality-driven politics, it is more constructive to examine the deeper structural dynamics at play. Over time, several unresolved bilateral concerns—ranging from border management and water-sharing issues to trade asymmetries—combined with broader perceptions of diplomatic imbalance, shaped public sentiment within Bangladesh. These developments underline the importance of sustained, responsive engagement between neighbouring states.

Border management has long been a flashpoint. The 4,096-km India-Bangladesh border is one of the world’s most densely populated and porous frontiers. Human rights groups documented at least 1,236 Bangladeshi fatalities attributed to Indian Border Security Force (BSF) actions between 2000 and 2020, with another 332 killings recorded from 2013 to 2023—an average of over 30 per year. In 2025 alone, during the interim government period, at least 34 Bangladeshis were killed, the highest in five years according to ‘Ain o Salish Kendra data’.

While both sides have repeatedly pledged “zero killings,” incidents persist, often linked to smuggling, cattle trade, or alleged illegal crossings. These tragedies fuel narratives of asymmetry and erode trust, even as formal mechanisms like the Coordinated Border Management Plan and director-general-level talks aim to address them through joint patrols, information-sharing, and non-lethal enforcement.

Water-sharing adds another layer of structural tension. Bangladesh and India share 54 transboundary rivers. The 1996 Ganges Water-Sharing Treaty, which allocates dry-season flows at Farakka, expires in December 2026. Dhaka has long complained of insufficient releases during lean periods, exacerbating salinity intrusion in the southwest, damage to the Sundarbans mangrove ecosystem, and agricultural losses. The Teesta River agreement, nearly finalised in 2011, remains stalled due to opposition from West Bengal. Climate change—reduced Himalayan glacier melt, erratic monsoons, and upstream damming—has intensified these disputes. Renegotiation of the Ganges treaty, incorporating updated hydrological data, joint basin management, and climate-resilient infrastructure, will be an early test for the new government and a signal of whether Delhi is prepared for equitable, science-based cooperation.

Trade asymmetries compound these grievances. Bilateral merchandise trade reached approximately $13–14 billion in recent years, but the balance heavily favours India. In FY 2024–25, India exported goods worth $11.46 billion to Bangladesh (up from $11.06 billion the previous year), while Bangladesh’s exports to India stood at $1.76 billion—a deficit exceeding $9 billion for Dhaka. Key Indian exports include cotton yarn (over $1.47 billion in 2024–25), rice, and petroleum products; Bangladesh sends readymade garments, jute, and footwear. Recent tit-for-tat restrictions—India’s land-route bans on Bangladeshi garments and processed foods in 2025, Bangladesh’s curbs on Indian yarn and rice imports—have raised costs and disrupted supply chains, particularly for Bangladesh’s garment sector, which relies on Indian inputs. Despite political friction, trade volumes have shown resilience, underscoring deep economic interdependence. Full utilisation of duty-free access under SAFTA, coupled with streamlined non-tariff measures, border haats expansion, and investment in cross-border infrastructure, could narrow the gap and generate mutual gains estimated in the billions.

For more than a decade, India and Bangladesh enjoyed a period of close cooperation under Sheikh Hasina and the Awami League. This partnership yielded tangible benefits: enhanced counterterrorism coordination (including joint operations against insurgent groups in the Northeast), improved regional connectivity (the Maitri Express, Akhaura-Agartala rail link, and inland water protocols), and relative political stability. Bilateral trade grew from under $5 billion in the early 2010s to over $13 billion. India extended lines of credit exceeding $8 billion for infrastructure. Yet the very success of this phase may have encouraged a degree of policy inertia. Over-reliance on a single political interlocutor left the relationship vulnerable when domestic realities shifted.

When student-led protests escalated in 2024, culminating in Hasina’s ouster and exile in India, New Delhi faced the complex challenge of balancing longstanding ties with evolving political realities. Decisions perceived within Bangladesh as overly aligned with the outgoing leadership—such as continued support during the unrest and reluctance to extradite Hasina—carried significant symbolic weight. In international relations, perceptions often matter as much as policy intent. Public discourse in Bangladesh increasingly framed India as backing an “authoritarian” regime, amplifying anti-India sentiment even as trade continued to rise.

The transition period that followed created opportunities for other regional actors to re-engage with Dhaka. Both Pakistan and China approached Bangladesh with calibrated diplomacy, emphasising continuity, economic cooperation, and openness to working with whichever government emerged.

China, in particular, maintained a consistent posture by separating economic engagement from domestic political outcomes. Since Bangladesh joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2016, Beijing has committed around $40 billion in projects and joint ventures, with disbursed investments exceeding $7 billion and construction contracts worth nearly $23 billion. Key deliverables include the Padma Bridge rail link, Payra power plant, Karnaphuli Tunnel, and power grid upgrades. These have boosted energy capacity and connectivity, though concerns about debt sustainability and environmental impact persist. China’s approach—pragmatic, project-focused, and non-interfering in internal politics—has positioned it as a reliable partner regardless of who rules in Dhaka.

Pakistan, meanwhile, pursued normalisation in a gradual and measured manner, mindful of historical sensitivities. High-level visits, trade delegations, and cultural exchanges have resumed, though volumes remain modest. The move reflects Dhaka’s desire for balanced ties rather than a pivot away from India.

India’s engagement during this phase, while present, appeared more cautious. This underscores a broader lesson in diplomacy: early, inclusive, and institution-focused outreach often proves more resilient than relationships anchored primarily in individual leaderships. Engaging opposition parties, civil society, and the bureaucracy during periods of uncertainty could have mitigated the perception of partisanship.

One notable development under the new government has been the election of Hindu representatives on BNP tickets—Goyeshwar Chandra Roy and Nitai Roy Chowdhury—along with two other minority candidates, signalling a commitment to inclusive governance. Hindus constitute approximately 8% of Bangladesh’s 170-million population (about 13.1 million people per the 2022 census). While the full cabinet (to be sworn in on 17 February 2026) is not yet announced, discussions within BNP circles include potential inclusion of minority and women leaders. This step reassures minority communities amid recent violence and reinforces Bangladesh’s secular constitutional ethos. Importantly, it demonstrates that pluralism and minority protection are not the preserve of any single political party. From a regional perspective, such measures help sustain confidence and reduce the scope for misinterpretation or escalation in bilateral relations.

Much commentary has framed Bangladesh’s evolving foreign policy in terms of alignment shifts. A more accurate interpretation is that Dhaka is pursuing strategic diversification—a common approach among mid-sized states in a multipolar world. Engagement with China on infrastructure, normalisation with Pakistan on trade and people-to-people ties, and continued cooperation with India on security, connectivity, and water need not be mutually exclusive.

This approach reflects pragmatism rather than ideological realignment. It also suggests that regional stability is best served when major powers acknowledge the legitimate autonomy of smaller neighbours. Mid-sized states like Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal increasingly hedge between India, China, and extra-regional actors (US, Japan, EU) to maximise development gains while preserving sovereignty.

In this evolving context, BIMSTEC assumes greater relevance. With its secretariat in Dhaka and its mandate spanning connectivity, trade, security, and sustainability, BIMSTEC offers a platform that transcends bilateral constraints. The BIMSTEC Master Plan for Transport Connectivity (adopted 2022) identifies 267 projects requiring $124 billion in investment through 2028, covering roads, railways, ports, inland waterways, and aviation. Intra-BIMSTEC trade remains low—around 6–7% of total trade (roughly $53 billion in 2023)—but potential is substantial. The recent Agreement on Maritime Transport Cooperation, power grid interconnection discussions, and the Bangkok Vision 2030 aim to create a “Prosperous, Resilient and Open BIMSTEC.”

For India, this represents an opportunity to reinforce leadership through collaboration rather than primacy—by addressing shared challenges (disaster management, blue economy), advancing projects like the India-Myanmar-Thailand Trilateral Highway, and responding constructively to member concerns on trade facilitation and rules of origin.

What’s next?

Several broader lessons emerge from this transition:

-

Institutional relationships matter. Durable partnerships extend beyond individual leaders and require engagement across political spectra. Regular Track-II dialogues, parliamentary exchanges, and youth/student programmes can build resilience.

-

Unresolved issues accumulate. Long-pending matters—whether water sharing (Ganges renewal in 2026, Teesta), border management (non-lethal policing, joint patrols), or market access—gradually shape public perceptions. Addressing them proactively through joint working groups and data transparency is essential.

-

Respect reinforces influence. Smaller states respond positively to engagement framed around equality and consultation. Symbolic gestures—high-level visits early in the new term, expedited project implementation, and sensitivity to domestic narratives—carry disproportionate weight.

-

Pluralism is strategic. Supporting democratic processes, minority rights, and inclusive governance, rather than specific outcomes, strengthens long-term credibility. India’s own democratic credentials and constitutional secularism provide a natural basis for partnership on these issues.

For Bangladesh, the new administration faces the challenge of translating its electoral mandate into effective governance amid economic pressures—garment sector recovery, inflation control, foreign exchange reserves, and coalition dynamics with allies. Restoring investor confidence, implementing constitutional reforms (two-term PM limit, bicameral parliament) approved in the referendum, and delivering on anti-corruption promises will be priorities.

For India, the moment calls for strategic adaptability—recognising that influence today is sustained through responsiveness, mutual benefit, and respect for sovereignty. Concrete steps could include:

-

Fast-tracking Teesta and Ganges negotiations with updated, jointly verified data and climate-adaptive mechanisms.

-

Expanding border haats, easing non-tariff barriers, and jointly developing economic corridors (e.g., via BIMSTEC).

-

Enhancing people-to-people ties through eased visas, educational exchanges, and cultural festivals.

-

Deepening security cooperation on counterterrorism, cyber threats, and maritime domain awareness in the Bay of Bengal.

-

Supporting Bangladesh’s diversification through trilateral projects (India-Japan-Bangladesh, India-US-Bangladesh) that avoid zero-sum framing.

Dr. Jaimine Vaishnav is a faculty of geopolitics and world economy and other liberal arts subjects, a researcher with publications in SCI and ABDC journals, and an author of 6 books specializing in informal economies, mass media, and street entrepreneurship. With over a decade of experience as an academic and options trader, he is keen on bridging the grassroots business practices with global economic thought. His work emphasizes resilience, innovation, and human action in everyday human life. He can be contacted on jaiminism@hotmail.co.in for further communication.

Dr. Jaimine Vaishnav is a faculty of geopolitics and world economy and other liberal arts subjects, a researcher with publications in SCI and ABDC journals, and an author of 6 books specializing in informal economies, mass media, and street entrepreneurship. With over a decade of experience as an academic and options trader, he is keen on bridging the grassroots business practices with global economic thought. His work emphasizes resilience, innovation, and human action in everyday human life. He can be contacted on jaiminism@hotmail.co.in for further communication.